The St. Francis Municipal Museum in Montefalco preserves the fresco cycle of Benozzo Gozzoli with stories from the life of St. Francis: a significant work not only for its undisputed artistic value but also because it is fundamental to understanding the iconographic reference of Sagrantino di Montefalco.

The museum of St. Francis represents a laboratory experience for the museum system. Between 1983 and 1990 it was restored by the Region, proceeding in small batches, and then reopened, entrusting its management to Museum System. It is a cooperative established in 1990 and based in Perugia. It works in various museums and circuits, providing qualified staff and organising a range of activities to enliven the museums.

In Montefalco, maintenance of the works and premises is ensured and exhibitions, concerts and other cultural activities are organised. Educational activity with the school is intense. The bookshop of the museum is rich in publications. The resident population, as well as tourists, have benefited from the activity, in line with the regional spirit of returning cultural assets to the citizens. This is an example of how the municipality of Montefalco is in step with the times.

Central apse of the former Church of St. Francis, now the Civic Museum of Montefalco

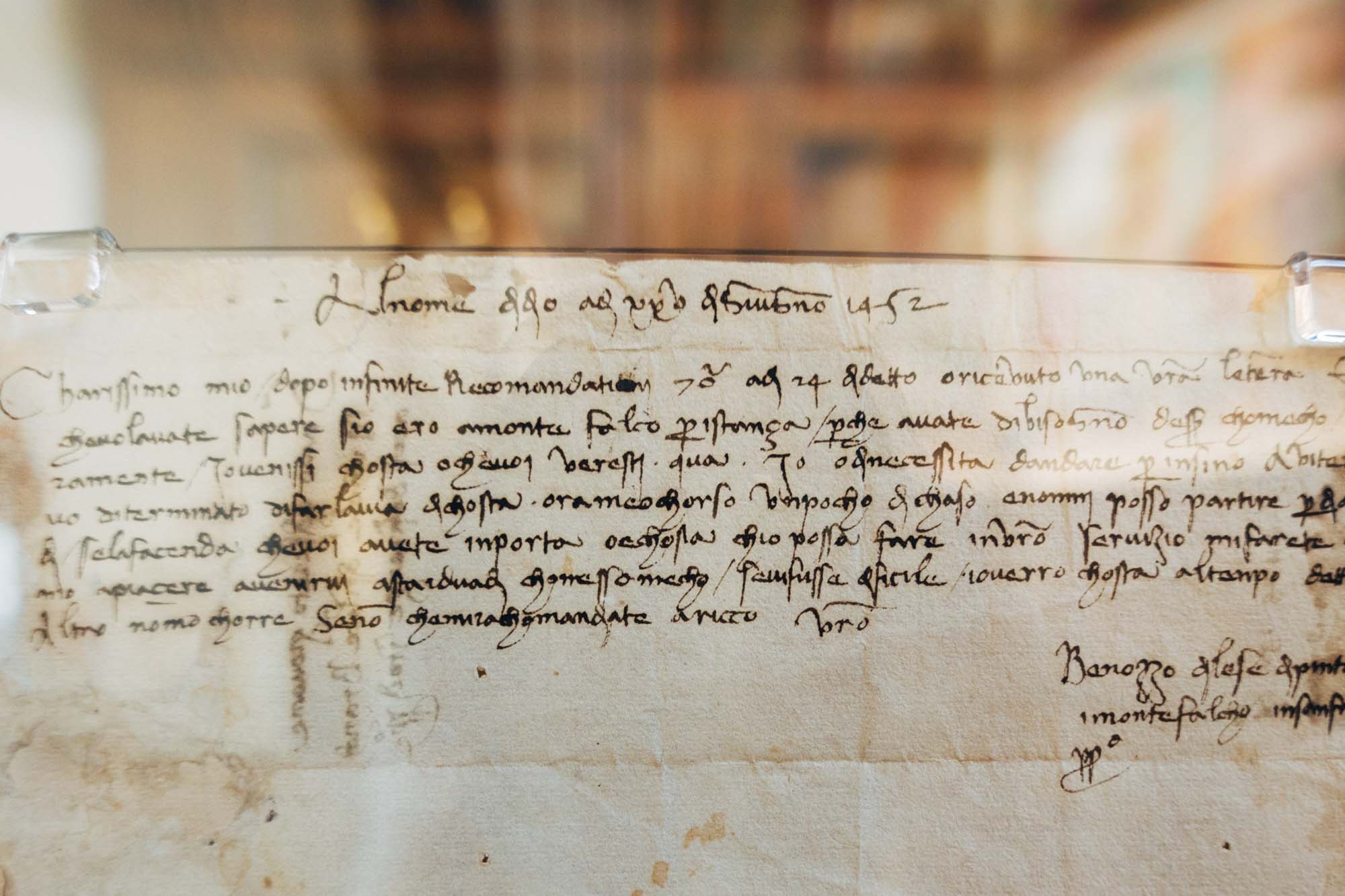

Benozzo Gozzoli, Stories from the Life of Saint Francis, Saints and Characters of the Franciscan Order, frescoes, 1452.

State of preservation and restoration.

Benozzo's cycle has faced a long and adventurous history of neglect, misunderstandings, and damage, which have seriously endangered the survival of this pictorial text, one of the most important in early Renaissance Italian painting.

The 1997 earthquake accentuated the state of instability of the vault, causing the partial detachment of a rib, but did not damage the frescoes. In general, the original parts of the cycle are largely preserved.

Commissioning.

The work was commissioned by Fra Jacopo da Montefalco, guardian of the Convent of St. Francis, who is mentioned in the dedicatory inscription and portrayed in the episode of the Blessing of the People of Montefalco. However, it was Friar Antonio da Montefalco, of the 'rival' Order of the Observants, who first called Benozzo to the Umbrian city. Antonio got to know the artist when he was working as Beato Angelico's assistant on the decorations in the Vatican. Appreciating his talents, he secured his presence in Montefalco in 1450, commissioning the artist to create both panel and fresco works for his church of San Fortunato. These works must evidently have met with Fra Jacopo's taste, if two years later Benozzo was called to work on the convent church of San Francesco. Benozzo moved unhurriedly from one church to another. The results that the painter achieved were profoundly different, as the message that the two patrons suggested to him was different.

Sources.

Called upon to illustrate the life of St. Francis, Benozzo used the great Giottesque model, but departed from it, as, at the probable suggestion of Friar Jacopo himself, he referred to two well-known Franciscan texts: the Legenda Maior by Bonaventure of Bagnoregio, which became the official biography of the saint from 1266, and the Legend of the Three Companions, which, focusing above all on the events in Assisi of Francis, was often an important source of inspiration for the depiction of the related scenes.

The cycle.

The life of the saint, from birth to death, is illustrated in twelve scenes arranged in three registers. The narrative proceeds, like an ideal elevation, from bottom to top and culminates in the vault with the glory of Saint Francis. The leitmotif of the cycle is the identification of Francis as the 'new Christ' (alter Christus), a central concept of Franciscan spirituality. The second register shows in a panel the scene of a dinner, whose protagonists are St. Francis and the Knight of Celano, by whom the saint had been invited. Two bottles are depicted on the table, one of water and one of red wine, and since there are frequent references to contemporary events and local characters, as in the scene of the Blessing of Montefalco and its people, the detail of the red wine could also be interpreted as a precise reference to the production of Sagrantino di Montefalco, a wine whose name derives precisely from its use in the imparting of the sacraments.

Style.

Benozzo found himself directing a painting site for the first time after having been employed by Angelico for many years in Florence, Rome and Orvieto. The great master's lesson is fundamental for the organisation of the cycle. In the adoption of particular compositional modules, in the predilection for certain human types and in the balance of colour, the memory of the years in which he was closest to Angelico guides Benozzo in this undertaking. However, as had been the case in his early Montefalco works in San Fortunato, the barely thirty-year-old Benozzo reveals absolutely original qualities in the Franciscan cycle: a more particularistic taste for narrative, a use of colour in a function that is both expressive and decorative.

Criticism.

Benozzo's Umbrian activity, completely forgotten by Vasari, was particularly appreciated during the 19th century, when a mystical interpretation was attempted. Benozzo's Franciscan Stories in Montefalco were of significant importance for the transformation of figurative culture in Umbria in the Proto-Renaissance sense.